Catégorie : Vitrine Méditerranéenne

Catégorie : Vitrine Méditerranéenne

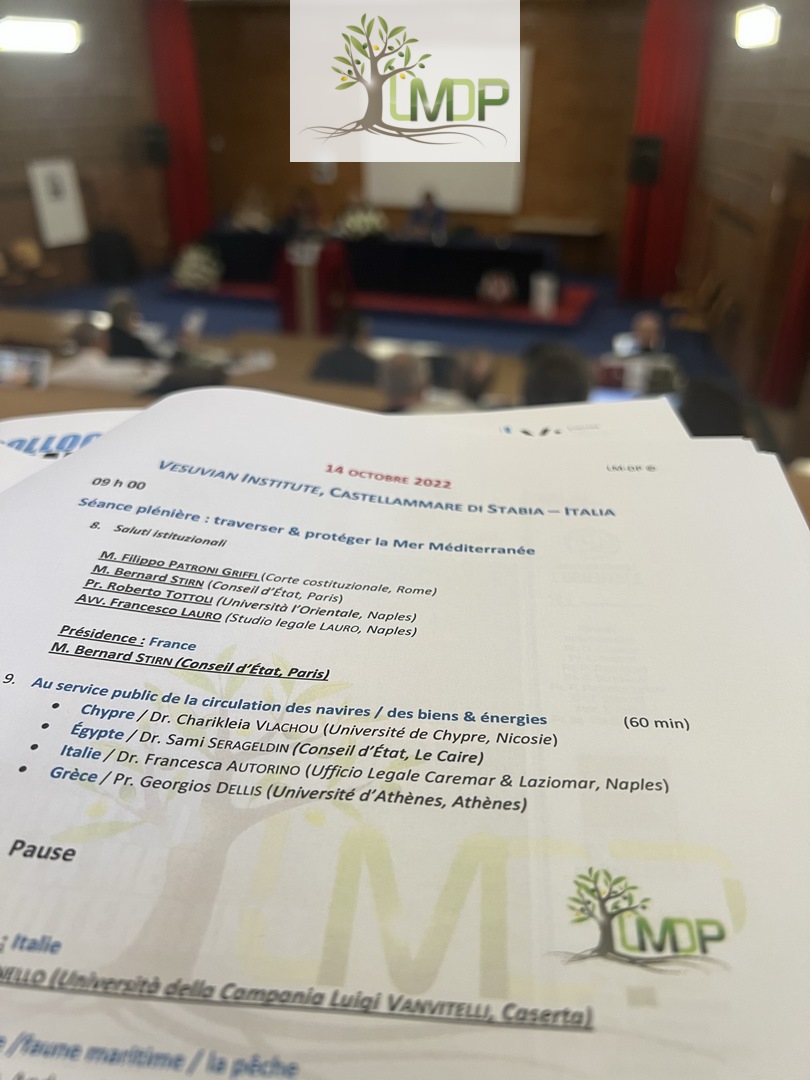

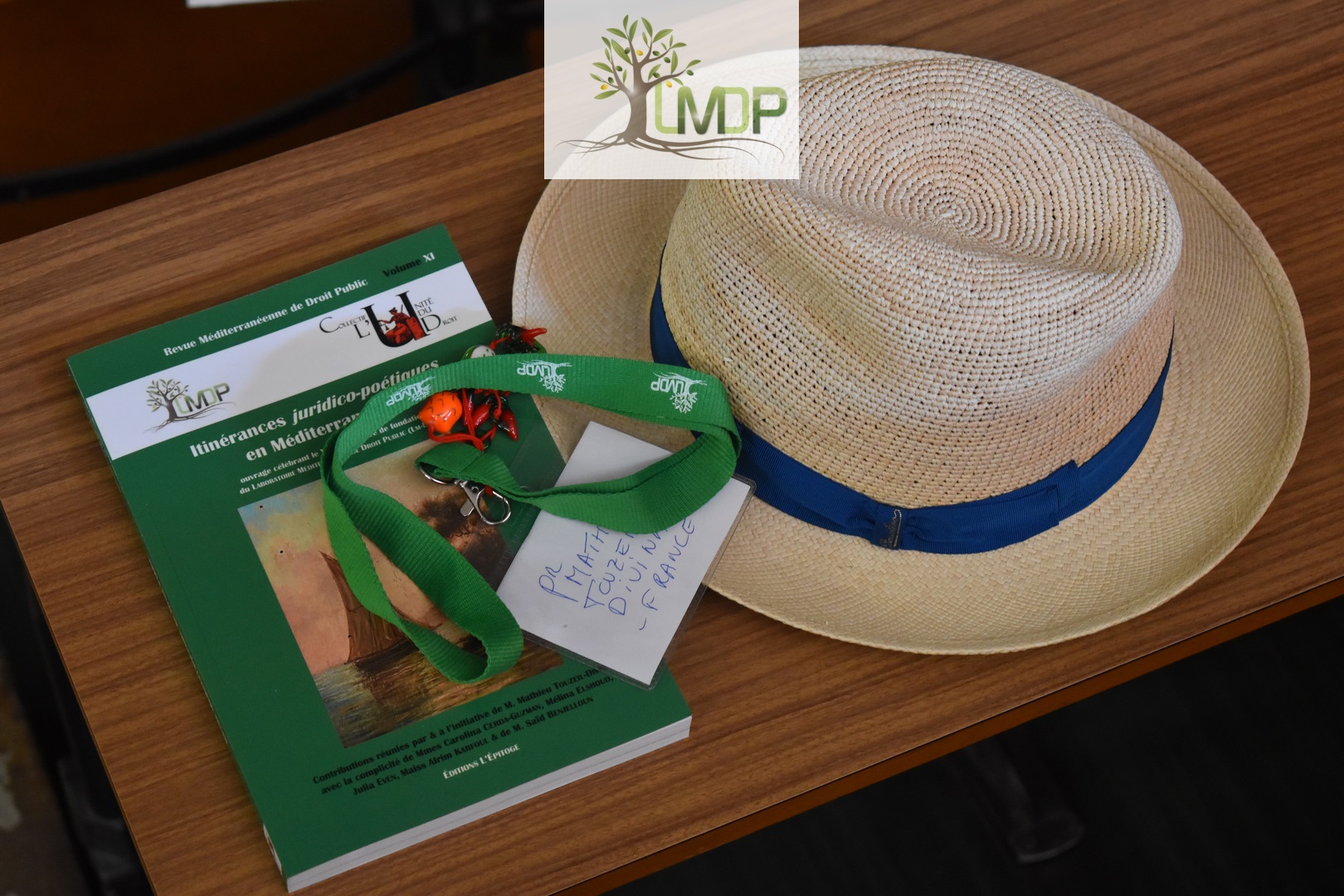

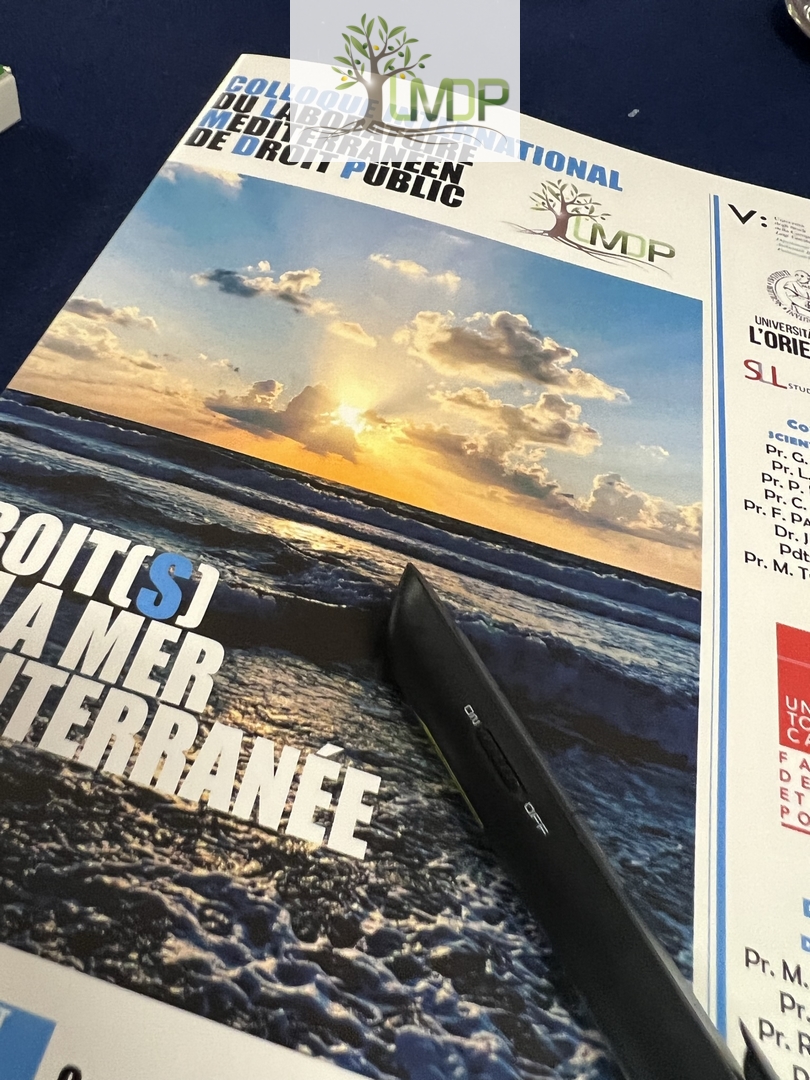

Reportage photographique du colloque de Naples 2/2 – 14 octobre 2022

Voici (en remerciant pour leurs yeux et leurs talents les Drs. Aurélie Tardieu & Mathieu Touzeil-Divina) les photographies prises lors des deux journées de colloque des 13 & 14 octobre 2022 lors des travaux sur le(s) droit(s) de la Mer Méditerranée à Castellammare di Stabia (Naples) (Italie). Liens vers : la présentation générale du colloque

DetailsReportage photographique du colloque de Naples 1/2 – 13 octobre 2022

Voici (en remerciant pour leurs yeux et leurs talents les Drs. Aurélie Tardieu & Mathieu Touzeil-Divina) les photographies prises lors des deux journées de colloque des 13 & 14 octobre 2022 lors des travaux sur le(s) droit(s) de la Mer Méditerranée à Castellammare di Stabia (Naples) (Italie). Liens vers : la présentation générale du colloque

DetailsRetours sur le colloque de Naples 2022

Liens vers : la présentation générale du colloque & son programme scientifique ; la bibliographie recommandée ; les photographies de la 1ère journée de colloque ; les photographies de la 2nde journée de travaux ; la réunion du Directoire du 13 octobre 2022 ; les photographies des instants de convivialité (réservé). 13 & 14 octobre

DetailsToulouse & mars en Méditerranée(s)

Ce sont les 14 & 15 mars 2022, à Toulouse qu’ont eu lieu les événements méditerranéens suivants et ce, grâce à la cellule toulousaine du LM-DP en étroit partenariat avec : l’Espace Culturel de l’Université Toulouse 1 Capitole (Mme Paule Géry) les Bibliothèques d’UT1 (M. Marcel Marty) la compagnie Jean Balcon (Toulouse) la cave Po’

DetailsProfesseurs en Méditerranée invités à Toulouse ! (annulation)

Annonce au 08 mars 2020 : malheureusement, pour des raisons de santé publique (#coronavirus), la venue des deux professeurs turc et italien, MM. Kaboglu et Iannello est reportée sine die. Les conférences et réunions des 09 – 10 et 11 mars en sont annulées (et reportées). L’Université Toulouse 1 Capitole (et notamment l’axe transformation(s) du

DetailsLouise Michel & le(s) droit(s)

Après un premier volet consacré à JAURES & le(s) droit(s) (cf. ICI & LA), le Collectif L’Unité du Droit, avec le soutien du Centre de Recherche en Droit, Antoine Favre de l’Université Savoie Mont-Blanc, du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public et du Centre de Droit de la Santé – Umr Ades de l’Université d’Aix-Marseille, vous

Details2nde édition des Eléments de bibliographie en droit public méditerranéen (le retour)

Revue Méditerranéenne de Droit Public2nde édition des Eléments de bibliographie(Rmdp n°06)dir. MM. Touzeil-Divina & Meyer Le Laboratoire Méditerranéenne de Droit Public engage la 2nde édition de ses Eléments bibliographiques de droit public méditerranéen (1ère éd. 2013). Vous trouverez ci-dessous l’exposé de quelques consignes à destination de tous ceux et de toutes celles désirant y contribuer.

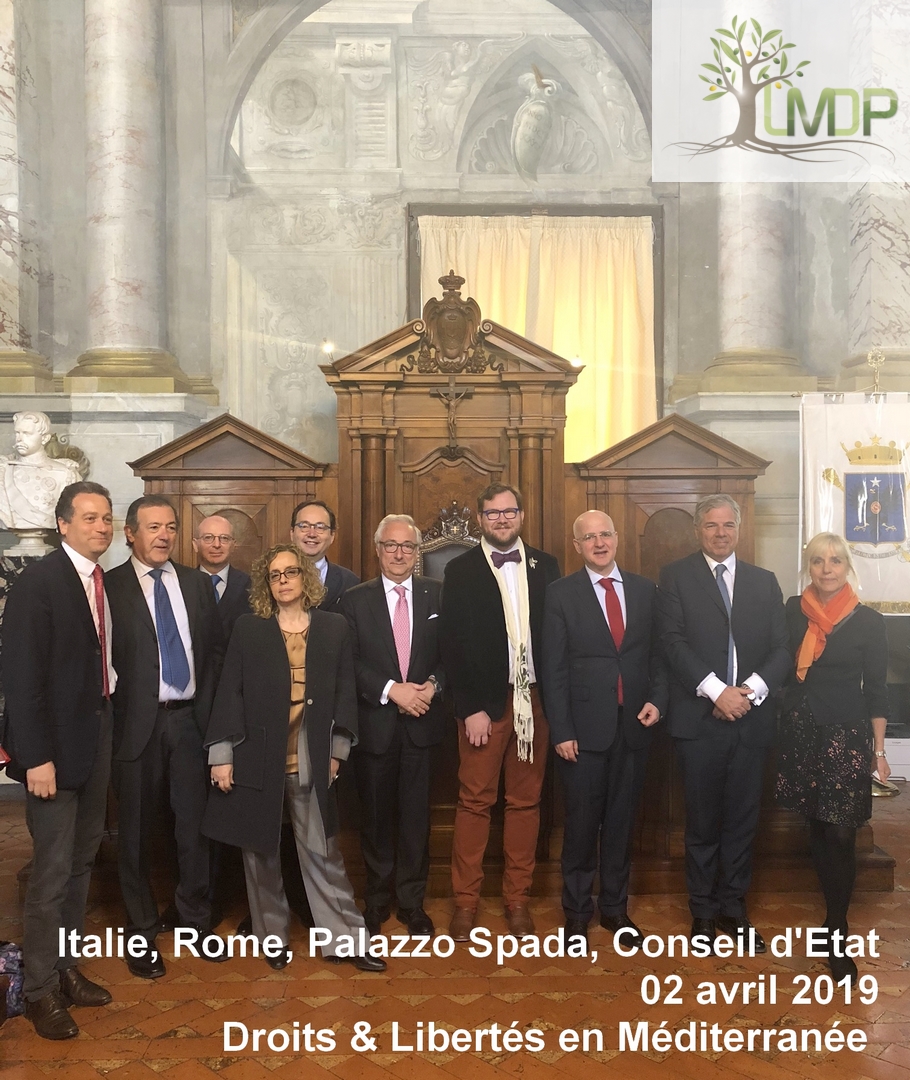

DetailsLe LMDP au Consiglio di Stato !

Ce mardi 2 avril 2019, à Rome, s’est tenue, en la présence et sous la modération de M. le Président du Conseil d’Etat, Filippo Patroni Griffi qui nous avait déjà fait l’honneur de sa présence lors du dernier colloque (2017) d’Athènes sur le(s) service(s) public(s) en Méditerranée, une très belle journée …placée sous le signe

DetailsDernier numéro de la RMDP

Il sortira – symboliquement – le 30 mars 2019 à Manosque, au Paraïs, dans la maison de Giono et ce, en partenariat avec l’association des Amis de Jean Giono, notre ouvrage anniversaire : L’Arbre, l’Homme & le(s) droit(s) ouvrage célébrant le 65e anniversaire de la parution de L’Homme qui plantait des arbres de Jean Giono

DetailsDiritti & Libertà nel Mediterraneo

Le 2 avril 2019, au Palais Spada, siège du Conseil d’Etat de la République italienne, à Rome, le Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public aura l’honneur de présenter ses activités en présence et sous la modération de M. le Président du Conseil d’Etat, Filippo Patroni Griffi qui nous avait déjà fait l’honneur de sa présence lors

DetailsRegards méditerranéens sur la Loi électorale libanaise du 16 juin 2017

Une conjugaison insolite du scrutin proportionnel avec vote préférentiel et répartition des sièges paritairement entre deux communautés et proportionnellement à l’intérieur de chacune d’elles L’exemple de la loi électorale libanaise du 16 juin 2017 par Hiam Mouannès, Maître de Conférences, HDR, Université Toulouse Capitole, Institut Maurice Hauriou Les élections législatives libanaises des 27 et 29

DetailsBonne & Méditerranéenne Année 2019 !

Le LM-DP est très heureux de vous présenter pour 2019 ses meilleurs voeux de fraternité & de droit public en Méditerranée ! Pour célébrer le passage à l’an neuf de 2019 voici quelques bonnes et heureuses nouvelles et quelques projets tout en Méditerranée : 2019, sera l’année de la sortie de la 2nde édition de

DetailsL’esprit de Mataroa

Convergences franco-helléniques en droit public et en pratiques administratives[1] Le LMDP est très heureux d’ouvrir avec cet article de Mme la professeure Ifigeneia Kamtsidou, Présidente du l’Ecole Nationale d’Administration Grecque (National Centre for Public Administration & Local Government (EKDDA)), une nouvelle tradition avec les voeux de 2019 : celle d’un article en droit public méditerranéen

DetailsA BRIEF HISTORY OF TURKISH CONSTITUTIONALISM

ECHOES OF THE PAST : A BRIEF HISTORY OF TURKISH CONSTITUTIONALISM Qu’est l’histoire? Un écho du passé dans l’avenir. Un reflet de l’avenir sur le passé[1]. (Victor Hugo, L’Homme qui rit, 1869) Introduction Even not noticed by its own actors, each social incident represents -in some way- major phenomena mainly determined and shaped by

DetailsSoutiens du LMDP aux actions napolitaines

Pour connaître le programme détaillé de ces journées napolitaine,s juridiques et en partie méditerranéennes consacrées aux services public locaux (et commerçants) il vous suffit de cliquer sur les images pour accéder aux PDF !

DetailsRentrée de la cellule toulousaine

C’est demain & on vous y attend … Tout est dans l’affiche 🙂 Alors il suffit de venir (entrée libre) en amphi Couzinet à 17.30 ce 08 novembre 2018.

DetailsSortie de la RMDP 8 ! Service(s) public(s) en Méditerranée

Le LMDP est heureux d’annoncer la publication aux éditions l’Epitoge du huitième numéro de sa Revue …. Il s’agit des actes publiés du colloque service(s) public(s) en Méditerranée ! Athènes (octobre 2017) Cet ouvrage est le huitième issu de la collection « Revue Méditerranéenne de Droit Public (RM-DP) ». En voici les détails techniques ainsi

DetailsLe LM-DP en Turquie

Le professeur Touzeil-Divina, directeur du LM-DP, a réalisé du 20 au 24 octobre 2018 un séjour en Turquie, à Istanbul, dans le cadre des activités du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public. Plusieurs temps forts ont ponctué ce séjour qui fait suite à quatre événements précédents : la création, en 2014, d’une équipe turque dirigée par

DetailsLiberté(s) ! En Turquie ? En Méditerranée !

Comme annoncé ici parmi plusieurs actions, c’est symboliquement, le jour même des élections présidentielles et législatives en Turquie, que les Editions l’Epitoge (du Collectif L’Unité du Droit), dont la diffusion est réalisée par les Editions juridiques Lextenso, publient ce 24 juin 2018 un nouveau numéro de la Revue Méditerranéenne de Droit Public réalisé en urgence

DetailsCréation de la 1ère cellule italienne du LMDP : à Naples

Le Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public est heureux de vous annoncer la naissance d’une nouvelle cellule (ou groupe) au sein de l’équipe italienne du LMDP : la cellule napolitaine. La création a eu lieu ce lundi 04 juin 2018 au Palazzo Serra di Cassano au coeur du prestigieux Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici. Etaient

DetailsSuccès pour le 2nd colloque international d’Athènes du LM-DP

Le deuxième colloque international du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public a eu lieu à Athènes les 19-20 octobre 2017. Il a rencontré un vif succès dans la lignée de celui réalisé en 2015 à Rabat. Au nom du Bureau du LM-DP, le pr. Touzeil-Divina remercie chacune et chacun des participant.e.s et des co-organisateurs et co-organisatrices

DetailsDéclaration d’Athènes (Directoire du LM-DP)

Réuni à Athènes les 19-20 octobre 2017, le directoire du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public émet les propositions suivantes concernant le(s) service(s) public(s) en Méditerranée. Le LM-DP constate la persistante actualité de la notion comme de la matérialité du service public dans les pays méditerranéens. En particulier, le LM-DP souligne l’importance du service public dans

DetailsPrésence au colloque du LM-DP de S.E. le Président Prokopios Pavlopoulos

Le 2e grand colloque international du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public a eu lieu à Athènes les 19-20 octobre 2017. Son programme est toujours disponible ICI. L’allocution de clôture du pr. Antoine Messarra qui en a fait la synthèse se trouve en ligne LA et vous pouvez également lire l’allocution du président Stirn ICI. Ci-dessous,

DetailsRéunion du Directoire du LM-DP (20 octobre 2017)

Le 2e grand colloque international du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public a eu lieu à Athènes les 19-20 octobre 2017. Son programme est toujours disponible ICI. L’allocution de clôture du pr. Antoine Messarra qui en a fait la synthèse se trouve en ligne LA et vous pouvez également lire l’allocution du président Stirn ICI. Ci-dessous,

DetailsSecond Colloque international du LM-DP : Athènes 19-20 oct. 2017

Le 2e grand colloque international du Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public a eu lieu à Athènes les 19-20 octobre 2017. Son programme est toujours disponible ci-dessous. L’allocution de clôture du pr. Antoine Messarra qui en a fait la synthèse se trouve en ligne LA et vous pouvez également lire l’allocution du président Stirn ICI. Vous

DetailsBienvenue au LM-DP !

Sous l’égide d’une association, le Collectif L’Unité du Droit, dont il fut un atelier indépendant, il a été proposé, à l’initiative du pr. Mathieu Touzeil-Divina, de constituer un observatoire ou laboratoire de droit public et ce, autour du bassin méditerranéen : le Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Public (Lm-Dp). Par suite, une dizaine de collègues – depuis toutes

DetailsColloque Droit & Religion en Méditerranée

Le pr. Touzeil-Divina a participé et publié, au nom du LM-DP, au présent colloque le 26 mai 2016 : Droit et Religion en MéditerranéeColloqueMardi 24 mai 2016, rue Polygnotou, Agora Romaine à Plaka, 17:00 Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Droit Publicen collaboration avecInstitut pour la Méditerranée (EPLO) 17.00 OUVERTURE Prof. Spyridon Flogaitis, Director, European Public Law Organization

DetailsColloque du LM-DP ; Rabat (octobre 2015) : Existe-t-il un droit public méditerranéen ?

Le premier colloque international du LM-DP a eu lieu les 28-29 octobre 2015 à Rabat. Il avait pour thème : Existe-t-il un droit public méditerranéen ? Vous trouverez sur le présent site concernant cet événement : 1. le rappel du programme du colloque (ci-dessous). 2. un premier compte rendu de la manifestation rédigé par M.

Details